Einar Garibaldi Eiríksson

TÍGRISDÝRASMJÖR

(útvarpspistill)

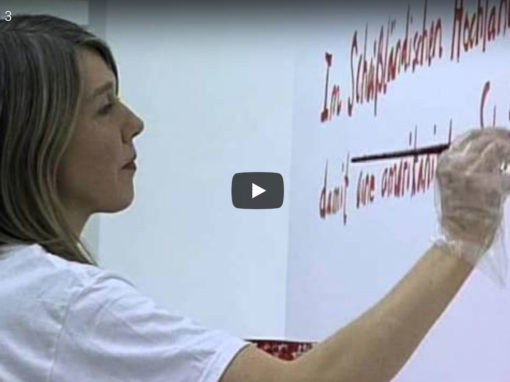

Verk Óskar sverja sig í ætt við þá samtímalist sem losað hefur sig við rammann og stöpulinn sem óvéfengjanlegan vitnisburð um sjálfan listhlutinn og frammi fyrir slíkum verkum vaknar oft og tíðum spurningin um: Hvað hafi orðið um listina? En verk Óskar leitast undan skilgreiningum af þessu tagi, hún er aðgerðarsinni er helgar sér svæði með gjörðinni, með þeirri skapandi og læknandi ástríðu sem engin bönd halda. Þegar hún boðar til málþings, leiðangra um hálendið eða kennir í skólastofunni, þá hugsar hún ekki um fyrirfram skilgreind mörk listarinnar. Hún er drifin áfram af hvöt sem vill umbreyta og gera sýnilegt hið hversdagslega. Hún lítur ekki á sýningarrýmið sem upphafið og einangrað rými fyrir listina –slitið úr samhengi sínu við umhverfið– heldur vill hún virkja almenningsrýmið til lækningar á því sem aflaga hefur farið í samfélagi okkar.

Ósk spyr sig ekki hvort hún sé að búa til eða framleiða listaverk, heldur felst aðgerðin sem slík í því að gera verk sem hreyfir, læknar og lagar frammi fyrir þeim öflum sem eyða, eigna sér og tileinka. Það er ekki hennar að gera verk sem þarf að skilgreina sem listaverk; hún framkvæmir einfaldlega vegna þess að hún finnur sig knúna til aðgerða. Svarið við spurningunni um hvað hafi orðið af listaverkinu, felst því í hvaða skilning við leggjum í gjörðir hennar; hvort að þeir sjálfsögðu og hversdagslegu hlutir sem verk hennar eru geti talist list og – ef svo er – þá hvaða merkingu það hafi fyrir okkur.

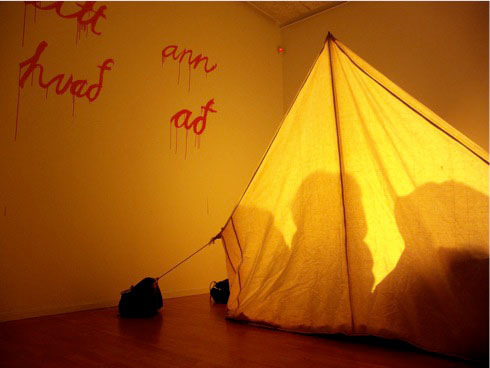

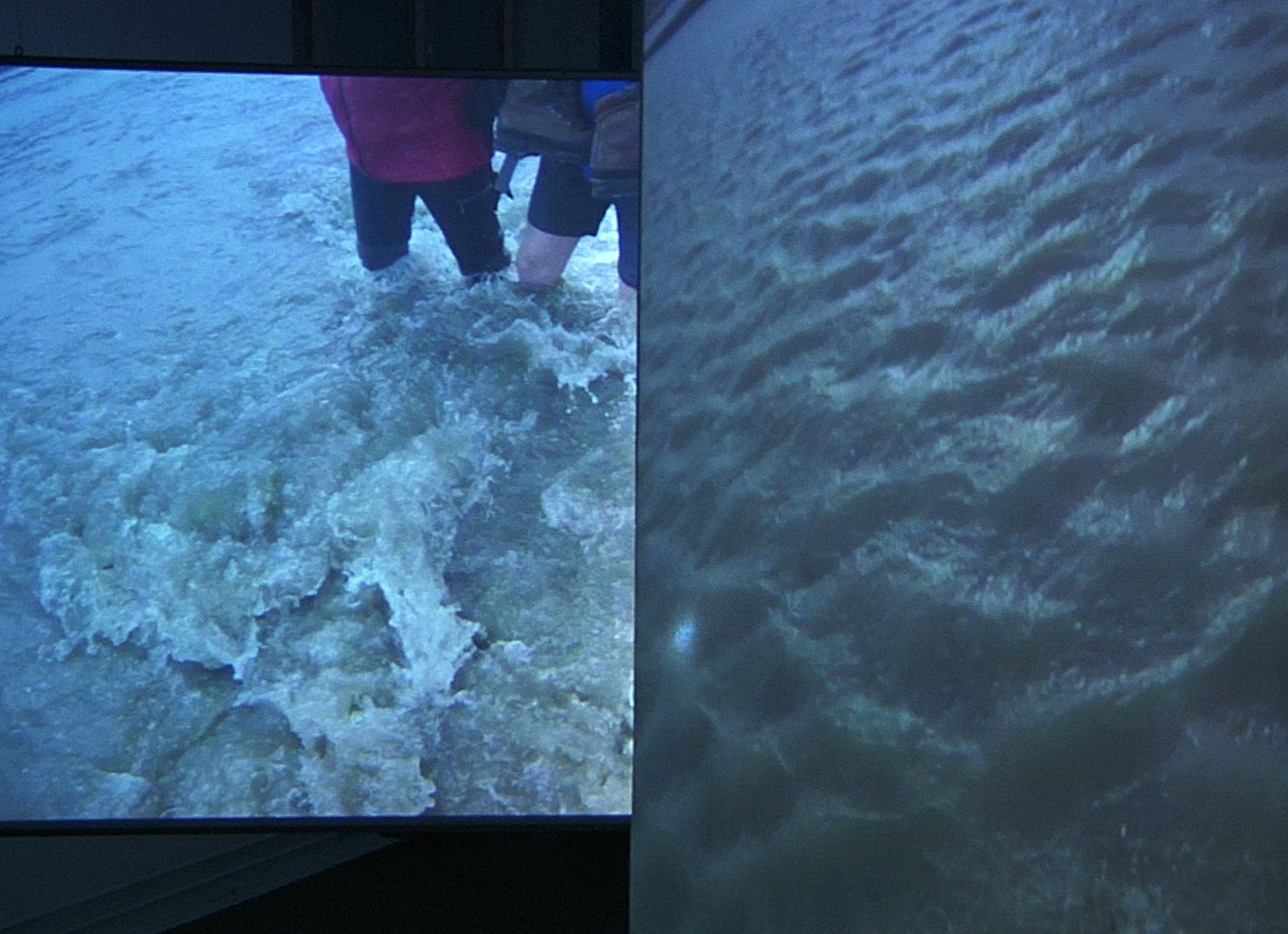

Þegar komið er inn á sýninguna er gengið inn í myrkvaðan sal og það fyrsta sem við augum blasir, er upplýst ferlíki sem líkt og ristir niður úr lofti sýningarsalarins. Þetta ferlíki líkist einna helst skipsskrokk sem dúkkað hefur þarna upp. Tilfinningin er einna líkust því að vera staddur neðansjávar og horfa undir skip og þannig dregur Ósk mann niður undir yfirborð sjávarins, ofan í höfnina handan við safnið.

Tilfinningin fyrir því að vera staddur á kafi styrkist þegar lengra er gengið inn í salinn, þar sem myrkrið umvefur áhorfendur, ásamt hljóði þar sem heyrist í manneskju líkt og að hlaupa hring eftir hring í kringum ferlíkið. Hljóðið er líkamleg og vitnar um áreynslu og ákefð, um leið og það er allt að því örvæntingarfullt svona innilokað í sjálft sig. Þessi innilokun er undirstrikuð með því að loka salinn frá götunni; því fyrir gluggum liggja hlerar og slagbrandar yfir, á meðan á þeim leika myndir sem varpað er með sýningarvél á flötinn, þar sem við greinum kappsfull sundtök manneskju er syndir án afláts að því er virðist út úr gömlu höfninni í Reykjavík.

Titill sýningarinnar Tígrisdýrasmjör vitnar í þekkt ævintýri, um dreng sem fer inn í skóg í sparifötunum sínum –sem hann er nýbúinn að fá– og hittir þar fyrir tígrisdýr sem vill hafa af honum jakkann. Ástæðan er einföld, tígrisdýrið vill verða voldugasta tígrisdýrið í skóginum. Sagan endar á því að af honum eru tekin öll fötin og tígrisdýrin takast á um völdin í skóginum, eltandi skottið hvert á öðru, hendandi af sér spjörunum, þar til að því kemur að þau bráðna og verða að smjöri. Og það er þetta Tígrisdýramsjör sem titill sýningarinnar vísar til.

Við okkur blasa fjölbreyttar og margslungnar táknmyndir; skip, örk, tjald, hús, heimili, gróðurhús, skjól, haf, höfn og kannski sjálft syndaflóðið. Og hér er sjálft sýningarrýmið líka tákngert, þar sem höfnin sjálf er dregin inn í salinn og tilfinningin sem fylgir því að ganga þangað inn er eins og að sökkva rólega á kaf ofan í gömlu höfnina.

Þessi sýning Óskar er í senn líknandi og endurnærandi; hún er opin og óræð um leið og hún er upplýsandi fyrir ástand eða sérstaka upplifun af því samfélagi sem umvefur okkur með hraða sínum og óreiðu. Þetta er ekki list sem er einangruð frá samfélaginu, hún er ekki skreyti, afþreying eða flótti. Hér leggjumst við líkt og undir feld; ráðum ráðum okkar um framtíðana, um það hvert beina eigi skipinu – kannski sjálfri Þjóðarskútunni. Sýningarsalurinn er líkt og vin, staður til að taka ákvarðanir, hugsa og framkvæma; nálægð, myrkur, höfgi grípur líkama manns sem sekkur rólega til botns, umvafinn köldu vatni hafnarinnar.

Hér deyr maður á vatni til að öðlast nýtt líf. Og það er hér á botni hafnarinnar sem sjálfur viskusteinninn kristallast. Við samsömumst ákefðinni í röddinni, könnumst við þessa manneskju sem hleypur hring eftir hring í ráðaleysi sínu. Hér fáum við tækifæri til að kynnast okkar leyndustu þrám og hugsunum, í veikri von um að geta umbreytt þeim í athafnir.