KAR

Undir

Bærinn stendur við breiðan fjörð sem iðar af mjúkum sjó. Hér er vítt til allra átta og uppúr blautu yfirborðinu mara óteljandi sker, hólmar og eyjar svo langt sem augað eygir. Sum hver eru grasivaxin eða þakin þangi og önnur hreinlega klöppin ber. Það sem skilur þau að eiga þau líka sameiginlegt. Lognið og þreifanlefgt i rfum orfin lli okkar og það er engu lkrta himininn eins langt og hann nær. Þegar sktaumlausar vindhviðurnar og sömuleiðis seltuna sem leggur undir sig allt. Undir niðri líða ósýnilegir fiskarnir þöglir um djúpin og hafa frá upphafi haldið lífi í fólkinu uppi á landinu í kring.

Innarlega við aðalgötuna sem liggur í gegnum bæinn stendur hús sem einu sinni var kvikmyndahús. Þau sem heimsækja það nú finna sér ekki lengur sæti í rökkrinu og láta sig dreyma með opin augu meðan birtan af tjaldinu baðar andlit þeirra. Nú ríkir hér annar og innilegri bjarmi og hann stafar frá eldfjöllum héðan og þaðan úr veröldinni. Hér er nefnilega safn sem hýsir muni og áþreifanleg sýni um eldgos og önnur jarðarinnar læti. Myndir af þeim undrum þegar jörðin skyndilega opnast og henni byrjar að blæða út í eitt. Það er hlýtt hérna inni og á sýningartjaldinu fangar okkur mynd af annars konar kvikuhólfi sem opnast blautt framan í okkur. Á milli loftsteina, gjalls, hraunmola úr eldgosum í áranna rás birtist okkur atburðarás og dæmi um samskipti dýrs og manns. Við erum bergnumin. Þau hjálpast að þannig að engu er líkara en þau hafi aldrei gert annað. Hér tekur eitt líf við öðru. Hvað eftir annað. Við erum vitni að fæðingum, sjálfum sauðburðinum. Stefnumótið er óvænt en heldur betur viðeigandi í nákvæmlega þessu húsi og á þessari eyju þar sem sköpin liggja leynt og ljóst þvert um hana miðja í einni heljarins und og fæðingarálmu steinanna ríkis. Eldfjöllin og sauðkindin eiga líka í nokkuð nánu sambandi þegar út er komið og birtan verður endalaus á fjöllum þar sem fátt annað er kvikt. Hún þræðir sig eftir þeim með sitt eina lamb eða tvö og treður sér slóða gegnum heiðbjarta þögnina. Sauðkindin er í senn einstæð móðirin og Maríumynd með sinn eingetna í miðri fjallshlíð.

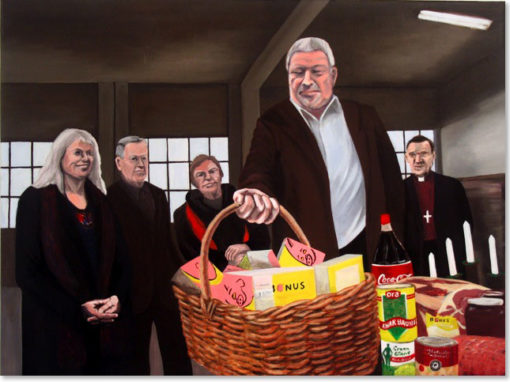

Steinsnar frá eldfjallasafninu liggur sundlaugin. Áður en gengið er til laugar blasa við myndir í anddyrinu. Þetta eru málverk á striga og þau endurvarpa því sem gerist á tjaldinu hinum megin götunnar. Þarna birtast þau aftur nýfæddu lömbin, hrein og rennandi blaut á hvítum striga. Litirnir eru svo næfurþunnir og birtan lifandi að það er engu líkara en þau hafi öll verið máluð með fersku legvatni.

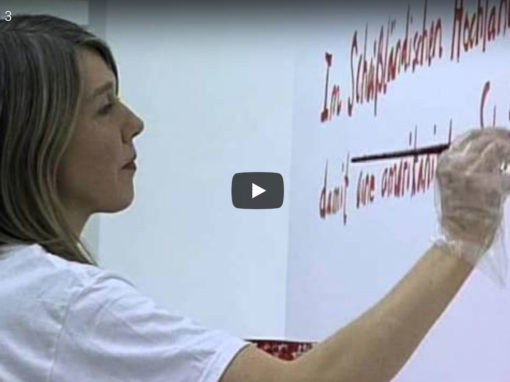

Höfundur þessara innsetninga er Ósk Vilhjálmsdóttir. Báðar eru þær margrar náttúru og lyklarnir að þeim sömuleiðis. Í þessu tilfelli felst einn þeirra hreinlega í orðsins hljóðan og uppruna. Nefnilega orðinu náttúra. Sjálfu lykilorðinu sem hann Jónas Hallgrímsson lét kyrrt liggja þegar hann var að þýða öll hin. Það hefur haft hrikalegar afleiðingar í samskiptum manns og umhverfis. Orðsifjar náttúru liggja alla leiðina til Miðjarðarhafsins, til latínunnar og sagnarinnar nascere. Gjörðarinnar að fæðast. Sennilega væri öðruvísi um að litast hér um slóðir ef þjóðskáldið hefði leitt þessa sögn inn á fæðingarveg íslenskunnar en ekki látið hana standa sem ókleifan vegg milli eyjaskeggja og ómælisins.

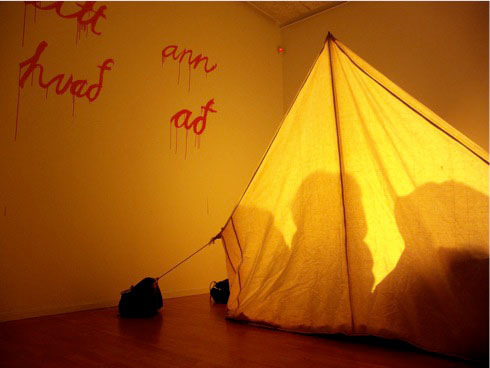

Innsetning Óskar Vilhjálmsdóttur er umhverfisverk og hverfist líkt og flest hennar verk um gjörninginn að sækja heim og kanna heima, um hreyfingu og ferli, um samskipti og óvænt samhengi. Þau fjalla um háttalag manns og náttúrur hans, hvernig við tökum þátt og kortleggjum land og þræðum borgir með hreyfingu og skynjunum líkamans. Hún býður okkur í leiðangur, að nema svæði sem fæðast og umbreytast stöðugt fyrir augum okkar. Ósk lýkur upp fyrir okkur nánasta umhverfi, hvernig við horfum og sjáum það hverfa og á hvaða hátt það birtist okkur síðan aftur í öðru ljósi og jafnvel í allt annarri mynd.

Haraldur Jónsson

Gashes

The town lies on a broad fjord astir with gentle seas. Here the view is wide-open in all directions and countless skerries, holms, and islands break the wet surface as far as the eye can see. Some are grassy or covered with seaweed and others are simply bare rock. What they have in common is also what divides them: still weathers and relentless winds as well as the brine that overwhelms everything. Below glide fish, silent and invisible in the depths; it is they who from the start have kept alive the people on the neighboring shore.

Tucked away on the town’s main thoroughfare is a building that once was a cinema. Those who visit it now no longer find a seat in the dark and lapse into a waking dream as light from the screen bathes their faces. Now a different and more profound glow reigns here, arising from volcanoes far and near around the world. For here we have a museum that houses relics and tangible evidence of eruptions and other turmoils of the earth. Images of the wondrous events when earth suddenly gapes and begins to bleed unstoppably. It is warm in here and we are arrested by an image on the movie screen, of a different kind of magma chamber opening wetly before our faces. In among meteorites and slag and ash from volcanic eruptions down through the years, a sequence of events unfolds before us, an example of the relations between human and animal. We stand riveted. Human and animal help each other in such a way that it seems they’ve done it all their lives. Here one life receives another. Again and again. We are witnessing births, the lambing itself. It’s an unexpected encounter but more than apropos in exactly this building and on this island, the genitalia of which lie hidden or in plain sight clear across the land in one enormous gash and mineral-kingdom birth canal. Volcanoes and sheep also have quite a close relationship outside the building, as the light, now unending, shines on mountains where there is scarcely another living thing. With a lamb or two in tow, ewes thread their way across the slopes, trampling paths through the clear-skied silence. The ewe is both a single mother and an image of Mary, with her only begotten one halfway up a mountainside.

It is a stone’s throw from the Volcano Museum to the swimming pool. As one enters to swim, images loom in the vestibule. These are paintings on canvas and they recast what happens on the screen across the street. Here are the newborn lambs again, clean and sopping-wet on white canvas. The paint is so whisper-thin and the light so vivid that it looks for the world as if they were all painted in fresh amniotic fluid.

The author of these installations is Ósk Vilhjálmsdóttir. Neither installation is simple in nature nor are the keys to understanding them. In this instance, one key resides purely in the sound and etymology of the word. The word nature, that is. The one key word that naturalist and poet Jónas Hallgrímsson left untouched, as náttúra, while finding Icelandic equivalents for all the rest. This has had horrible consequences for the relations between humans and the environment. The etymology of nature extends all the way to the Mediterranean, to Latin and the verb nascere. The act of being born. Things might well look different around here if the national poet had drawn this verb through the birth canal of the Icelandic language instead of letting it stand like an unscalable wall between islanders and the ineffable.

Ósk Vilhjálmsdóttir’s installation is an environmental work and, like most of her work, centers on a performance of visiting and exploring worlds, on motion and process, on relationships and surprising contexts. Her work treats the natures and customs of human beings, how we join in, map land, and navigate cities through our bodies’ motion and perception. Ósk invites us on an expedition to occupy regions that are continually born and transformed before our eyes. She discloses to us our near environment, how we regard it and see it disappear and in what way it later reappears to us in a different light or even a completely different form.

Haraldur Jónsson

projects