Tigerbutter

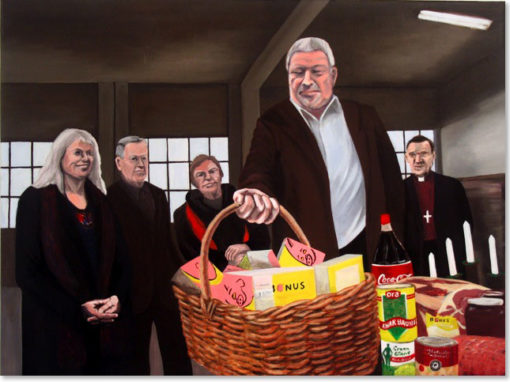

At the bottom and running in circles. Biting in tails. Registered on a ship that hangs on fixed strange place. Is this a greenhouse on fire? Or camping tent in the autumn dusk, is anyone there? We have always been on this ship. It has always been hanging around there. Inside it holds animals and humans, a whole world.

Einar Garibaldi Eiríksson

TÍGRISDÝRASMJÖR

(útvarpspistill)

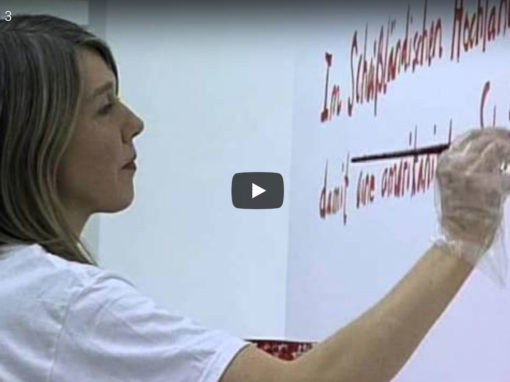

Verk Óskar sverja sig í ætt við þá samtímalist sem losað hefur sig við rammann og stöpulinn sem óvéfengjanlegan vitnisburð um sjálfan listhlutinn og frammi fyrir slíkum verkum vaknar oft og tíðum spurningin um: Hvað hafi orðið um listina? En verk Óskar leitast undan skilgreiningum af þessu tagi, hún er aðgerðarsinni er helgar sér svæði með gjörðinni, með þeirri skapandi og læknandi ástríðu sem engin bönd halda. Þegar hún boðar til málþings, leiðangra um hálendið eða kennir í skólastofunni, þá hugsar hún ekki um fyrirfram skilgreind mörk listarinnar. Hún er drifin áfram af hvöt sem vill umbreyta og gera sýnilegt hið hversdagslega. Hún lítur ekki á sýningarrýmið sem upphafið og einangrað rými fyrir listina –slitið úr samhengi sínu við umhverfið– heldur vill hún virkja almenningsrýmið til lækningar á því sem aflaga hefur farið í samfélagi okkar.

Ósk spyr sig ekki hvort hún sé að búa til eða framleiða listaverk, heldur felst aðgerðin sem slík í því að gera verk sem hreyfir, læknar og lagar frammi fyrir þeim öflum sem eyða, eigna sér og tileinka. Það er ekki hennar að gera verk sem þarf að skilgreina sem listaverk; hún framkvæmir einfaldlega vegna þess að hún finnur sig knúna til aðgerða. Svarið við spurningunni um hvað hafi orðið af listaverkinu, felst því í hvaða skilning við leggjum í gjörðir hennar; hvort að þeir sjálfsögðu og hversdagslegu hlutir sem verk hennar eru geti talist list og – ef svo er – þá hvaða merkingu það hafi fyrir okkur.

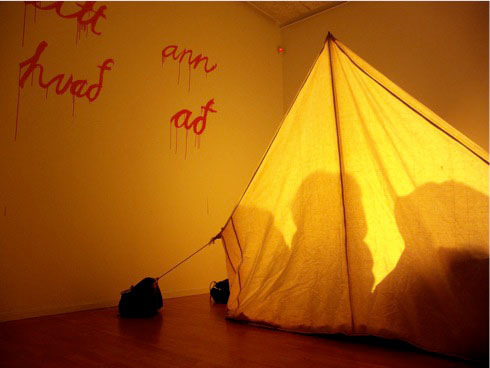

Þegar komið er inn á sýninguna er gengið inn í myrkvaðan sal og það fyrsta sem við augum blasir, er upplýst ferlíki sem líkt og ristir niður úr lofti sýningarsalarins. Þetta ferlíki líkist einna helst skipsskrokk sem dúkkað hefur þarna upp. Tilfinningin er einna líkust því að vera staddur neðansjávar og horfa undir skip og þannig dregur Ósk mann niður undir yfirborð sjávarins, ofan í höfnina handan við safnið.

Tilfinningin fyrir því að vera staddur á kafi styrkist þegar lengra er gengið inn í salinn, þar sem myrkrið umvefur áhorfendur, ásamt hljóði þar sem heyrist í manneskju líkt og að hlaupa hring eftir hring í kringum ferlíkið. Hljóðið er líkamleg og vitnar um áreynslu og ákefð, um leið og það er allt að því örvæntingarfullt svona innilokað í sjálft sig. Þessi innilokun er undirstrikuð með því að loka salinn frá götunni; því fyrir gluggum liggja hlerar og slagbrandar yfir, á meðan á þeim leika myndir sem varpað er með sýningarvél á flötinn, þar sem við greinum kappsfull sundtök manneskju er syndir án afláts að því er virðist út úr gömlu höfninni í Reykjavík.

Titill sýningarinnar Tígrisdýrasmjör vitnar í þekkt ævintýri, um dreng sem fer inn í skóg í sparifötunum sínum –sem hann er nýbúinn að fá– og hittir þar fyrir tígrisdýr sem vill hafa af honum jakkann. Ástæðan er einföld, tígrisdýrið vill verða voldugasta tígrisdýrið í skóginum. Sagan endar á því að af honum eru tekin öll fötin og tígrisdýrin takast á um völdin í skóginum, eltandi skottið hvert á öðru, hendandi af sér spjörunum, þar til að því kemur að þau bráðna og verða að smjöri. Og það er þetta Tígrisdýramsjör sem titill sýningarinnar vísar til.

Við okkur blasa fjölbreyttar og margslungnar táknmyndir; skip, örk, tjald, hús, heimili, gróðurhús, skjól, haf, höfn og kannski sjálft syndaflóðið. Og hér er sjálft sýningarrýmið líka tákngert, þar sem höfnin sjálf er dregin inn í salinn og tilfinningin sem fylgir því að ganga þangað inn er eins og að sökkva rólega á kaf ofan í gömlu höfnina.

Þessi sýning Óskar er í senn líknandi og endurnærandi; hún er opin og óræð um leið og hún er upplýsandi fyrir ástand eða sérstaka upplifun af því samfélagi sem umvefur okkur með hraða sínum og óreiðu. Þetta er ekki list sem er einangruð frá samfélaginu, hún er ekki skreyti, afþreying eða flótti. Hér leggjumst við líkt og undir feld; ráðum ráðum okkar um framtíðana, um það hvert beina eigi skipinu – kannski sjálfri Þjóðarskútunni. Sýningarsalurinn er líkt og vin, staður til að taka ákvarðanir, hugsa og framkvæma; nálægð, myrkur, höfgi grípur líkama manns sem sekkur rólega til botns, umvafinn köldu vatni hafnarinnar.

Hér deyr maður á vatni til að öðlast nýtt líf. Og það er hér á botni hafnarinnar sem sjálfur viskusteinninn kristallast. Við samsömumst ákefðinni í röddinni, könnumst við þessa manneskju sem hleypur hring eftir hring í ráðaleysi sínu. Hér fáum við tækifæri til að kynnast okkar leyndustu þrám og hugsunum, í veikri von um að geta umbreytt þeim í athafnir.

Osk’s work harks back to those forms of contemporary art which eliminated the need to use a frame or a plinth to identify the art object itself. Encountering such works, people tend to ask: But what became of the Art? Ósk’s works, however, sidestep such distinctions. She is an activist whose acts claim their space through a creative, healing passion which nothing can hold back. When she announces a workshop, organizes a highland trek, or teaches a class, she does not care about pre-existing limits to art. She is driven by an urge to transform and render visible what is taken for granted. Thus, she does not see the exhibition space as an exalted and isolated space for art, divorced from its context; she wants to activate the public space and heal what has gone awry in our society.

Ósk does not ask herself whether she is making or producing works of art. Her action consists in creating a work which moves, heals and mends in the face of the powers which destroy, appropriate and co-opt. Her intent is not to create pieces that need to be defined as works of art; she simply takes action because she feels impelled to act. The answer to the question as to what became of the art object depends on our interpretation of her actions; whether the self-evident and ordinary objects of her work can be classified as Art, and, if so, what significance they have for us.

Ósk’s exhibition at the Hafnarhúsið surprises in many ways. Clear, as ever, is her strong need to mend, improve and salve wherever things have gone wrong. Now, however, this need is manifest in a range of dream-like symbolic images, where fantastic associations are continually revealed to the viewer. On arrival, one enters a darkened hall where the first thing to meet the eye is an illuminated hulk which appears to have punched through the ceiling. Resembling nothing so much as the hull of a ship, it looks as though it has somehow materialized out of nowhere. It feels as though we are beneath the surface of the water, looking up at the ship’s hull. Thus, Ósk pulls us into the water, down into the harbor just beyond the museum.

The sense of submersion grows more intense as one proceeds into the room, where darkness envelops the audience along with a sound of a person seemingly running in circles around the leviathan. The physical presence of the sound conveys a sense of intense exertion and a near-desperate sense of being shut in upon itself. The claustrophobia is enhanced by isolating the exhibition hall from the street. The windows are shuttered and barred, while on the shutters play images in which we can make out the strenuous swim strokes of a person apparently swimming ceaselessly out to sea from Reykjavik’s Old Harbor.

Ósk is known for her hard-hitting pieces where she takes on the big issues of her time. In this show, however, she moves to more symbolic ground, touching strings more lyrical than has been her wont. This time, she did not feel it right to put on meetings or raise a commotion over any particular issue, for; after all, such activity is all around us. The show’s title, Tiger Butter, refers to the familiar tale of a boy who, wearing his newly acquired best clothes, wanders into the woods, where he encounters a tiger who wants to take his jacket away from him. The reason is simple – the tiger wants to become the most powerful tiger in the forest. By the end of the story, all the boy’s clothes have been taken away from him, while tigers engage in a struggle for control of the forest, chasing each others’ tails, reducing the clothes to rags and casting them aside, eventually melting and turning into butter – the Tiger Butter of the show’s title.

Before us are arrayed diverse and complex symbols: a ship, an ark, a tent, a house, a home, a greenhouse; shelter, sea, harbor, even the Flood itself. Indeed, even the exhibition space itself has taken on a symbol- ism, pulling in the very harbor, so that entering the space feels like a slow sinking into the depths of the Old Harbor.

Ósk’s show brings both grace and refreshment; it is open and indeterminate while illuminating the stateor experience of the society with its ever-present speed and chaos. This is not art apart from society; it is neither ornament, entertainment nor escapism. Here, we take time to ponder; we confer on the future and on which course to set for the ship – perchance the Ship of State itself. The exhibition hall is like an oasis; a place to make decisions, to think and to act; closeness, dark, drowsiness takes hold of one’s body as it slow- ly sinks to the bottom in the embrace of the cold waters of the harbor.

Here, one dies by water to attain a new life. And it is here, on the harbor floor, that the Water Stone of the Wise – the Philosopher’s Stone itself – takes form. We identify with the insistence of the voice; we are familiar with this person running around in endless circles of confusion and perplexity. Here we may discover our most hidden thoughts and desires and the faint hope of transforming them into action. The only thing left is to thank Ósk for bathing us in Tiger Butter.

projects